Programme 3 of the Southeast Asian Short Film Competition of this year’s Singapore International Film Festival (SGIFF) contains four very different stories, each one compelling in ways that the others were not. Tonally, they are all peaceful and reflective, with each filmmaker choosing to use soothing imagery and sound design in order to calmly relay their stories. From the artificiality of film making in Tulapop Saenjaroen’s People on Sunday and the reflective recollection of past memories in Joanna Vasquez Arong’s To Calm the Pig Inside, to the dissection of divorce from a young boy’s perspective in Mathias Choo’s Rocketship and the straddling of fact and fiction in Riar Rizaldi’s Tellurian Drama, the short films take you on a journey through different people’s minds in a way that truly picks apart how specific people think, deal with trauma and understand the world around them.

What really brings the four pieces together is their serenity. There are no high action set pieces to be found anywhere, and, while not all are equally easy to sit through, each short is not difficult to digest. The collection is very accessible and, while nothing truly life altering is ever presented, feels meaningful in a very intimate and personal sense. In a cinematic ecosystem of lots of action, tension, and stress, these short films are refreshing in their simplicity.

People On Sunday (dir. Tulapop Saenjaroen)

Judging from Tulapop Saenjaroen’s previous work, I expected People on Sunday to be as deliciously surreal as short films can get. I was not disappointed.

People on Sunday is difficult to describe. It does not follow a basic plot line. It is really two stories at once, one a film paying tribute to the 1930 silent film Menschen am Sonntag (“People on Sunday” in German), and another documenting the filmmaking process. With each shot of the “real” film presented, we are also shown the work that needs to be put into it in order to create the image. The short film hence breaks the illusion of cinema by putting the artificiality of film at its forefront.

In the film, Saenjaroen lets the viewer into his head. He explains his apprehension towards being onscreen and watched. His narration juxtaposes heavily against the images presented, the amateur actors’ excitement at appearing in a film and their director’s dread at being on camera being completely opposing views. It is really intriguing to watch Saenjaroen simultaneously pay tribute to filmmaking and examine his personal vendetta against video documentation.

One of the cleverest parts of People on Sunday is its self-referential elements. Everything that is presented is in some way returned to later on or related to an external piece of work. Saenjaroen rewards the focused audience member. Every bizarre element presented in the beginning of the film is returned to and re-examined from a different perspective. The closing scene is, in essence, a re-creation of the opening sequence.

While being incredibly different from his previous short film A Room with a Coconut View (which was screened at the 29th SGIFF), People on Sunday retains Saenjaroen’s consistently unorthodox tone and feeling, albeit much darker in this film. Each of the stylistic design choices feel like signature elements, or as close to a signature element something can be within just two films. Saenjaroen’s filmmaking style is becoming even more interesting.

To Calm The Pig Inside (dir. Joanna Vasquez Arong)

To Calm the Pig Inside feels like listening to a relative recount their personal memories as they flip through old photo albums. In her short film, Joanna Vasquez Arong deliberates upon the effect the storm surge Yolanda had on a small Filipino seaside city, and recounts the devastating effect that the storm had on herself on the people around her.

The short film’s namesake comes from a mythical pig inside the earth, Buwa, whose anger trembles the earth and causes earthquakes. When earthquakes occur, people shout his name in order to “calm the pig inside the earth”. But there is no alternative for calming the winds of a typhoon and soothing a storm surge. The destruction of the storm Yolanda almost seems to be able to obliterate mythology as well.

Presented entirely in black and white, To Calm the Pig Inside creates the illusion of being set in the past. Arong seems to have made this choice deliberately, since the storm surge Yolanda occurred in November 2013, and it is safe to assume that most of the footage captured of the storm was in full colour. What could be the motivation behind the black and white choice? It could be argued that this gives the story a distinct personality, but I would interpret it as being a conscious decision to leave the events in the past. Such a painful event deserves to be separated from a brighter and more hopeful future.

The piece is maliciously soothing in an almost hypnotic way. A calm voiceover explaining the destruction of homes and loss of security is too comforting for the horrors which it is describing. The film does not come without criticism, and sometimes it feels too lacklustre and passive to really give a real insight into the effect of the storm surge. By keeping everything at arm's length, things are a little too far out of reach to make a strong connection.

Some of the most haunting material in Arong’s film are the stills of children’s drawings depicting their experiences with the storm surge. The imprints of sad faces on stick figures surrounded by floating bodies, drawn with the rapidness and desperation of a child, feels like looking at the exact drawings which stripped away a part of their childhoods. As the sounds of waves crashing and wind blowing is heard in the background, the sequence is deeply upsetting.

To Calm the Pig Inside is hauntingly beautiful. Arong does an expert job in providing a story that is held up purely by narration, black and white stills and footage and minimalistic sound design, although it does leave me wanting even more.

Rocketship (dir. Mathias Choo)

Though Rocketship first presents itself as a story about divorce from a young boy’s perspective, as the film progresses, it becomes clear that this is not the case. It is less about divorce and much more about a powerful mother-son relationship. Mathias Choo’s cinematography choices are simple, symmetrical and easy to digest, which makes the film very pleasurable to view. And while the reality of the world Samuel and his mother inhabit feel very fictionalised, the emotions which they feel are very real.

What really brings the four pieces together is their serenity. There are no high action set pieces to be found anywhere, and, while not all are equally easy to sit through, each short is not difficult to digest. The collection is very accessible and, while nothing truly life altering is ever presented, feels meaningful in a very intimate and personal sense. In a cinematic ecosystem of lots of action, tension, and stress, these short films are refreshing in their simplicity.

People On Sunday (dir. Tulapop Saenjaroen)

Judging from Tulapop Saenjaroen’s previous work, I expected People on Sunday to be as deliciously surreal as short films can get. I was not disappointed.

People on Sunday is difficult to describe. It does not follow a basic plot line. It is really two stories at once, one a film paying tribute to the 1930 silent film Menschen am Sonntag (“People on Sunday” in German), and another documenting the filmmaking process. With each shot of the “real” film presented, we are also shown the work that needs to be put into it in order to create the image. The short film hence breaks the illusion of cinema by putting the artificiality of film at its forefront.

In the film, Saenjaroen lets the viewer into his head. He explains his apprehension towards being onscreen and watched. His narration juxtaposes heavily against the images presented, the amateur actors’ excitement at appearing in a film and their director’s dread at being on camera being completely opposing views. It is really intriguing to watch Saenjaroen simultaneously pay tribute to filmmaking and examine his personal vendetta against video documentation.

One of the cleverest parts of People on Sunday is its self-referential elements. Everything that is presented is in some way returned to later on or related to an external piece of work. Saenjaroen rewards the focused audience member. Every bizarre element presented in the beginning of the film is returned to and re-examined from a different perspective. The closing scene is, in essence, a re-creation of the opening sequence.

While being incredibly different from his previous short film A Room with a Coconut View (which was screened at the 29th SGIFF), People on Sunday retains Saenjaroen’s consistently unorthodox tone and feeling, albeit much darker in this film. Each of the stylistic design choices feel like signature elements, or as close to a signature element something can be within just two films. Saenjaroen’s filmmaking style is becoming even more interesting.

To Calm The Pig Inside (dir. Joanna Vasquez Arong)

To Calm the Pig Inside feels like listening to a relative recount their personal memories as they flip through old photo albums. In her short film, Joanna Vasquez Arong deliberates upon the effect the storm surge Yolanda had on a small Filipino seaside city, and recounts the devastating effect that the storm had on herself on the people around her.

The short film’s namesake comes from a mythical pig inside the earth, Buwa, whose anger trembles the earth and causes earthquakes. When earthquakes occur, people shout his name in order to “calm the pig inside the earth”. But there is no alternative for calming the winds of a typhoon and soothing a storm surge. The destruction of the storm Yolanda almost seems to be able to obliterate mythology as well.

Presented entirely in black and white, To Calm the Pig Inside creates the illusion of being set in the past. Arong seems to have made this choice deliberately, since the storm surge Yolanda occurred in November 2013, and it is safe to assume that most of the footage captured of the storm was in full colour. What could be the motivation behind the black and white choice? It could be argued that this gives the story a distinct personality, but I would interpret it as being a conscious decision to leave the events in the past. Such a painful event deserves to be separated from a brighter and more hopeful future.

The piece is maliciously soothing in an almost hypnotic way. A calm voiceover explaining the destruction of homes and loss of security is too comforting for the horrors which it is describing. The film does not come without criticism, and sometimes it feels too lacklustre and passive to really give a real insight into the effect of the storm surge. By keeping everything at arm's length, things are a little too far out of reach to make a strong connection.

Some of the most haunting material in Arong’s film are the stills of children’s drawings depicting their experiences with the storm surge. The imprints of sad faces on stick figures surrounded by floating bodies, drawn with the rapidness and desperation of a child, feels like looking at the exact drawings which stripped away a part of their childhoods. As the sounds of waves crashing and wind blowing is heard in the background, the sequence is deeply upsetting.

To Calm the Pig Inside is hauntingly beautiful. Arong does an expert job in providing a story that is held up purely by narration, black and white stills and footage and minimalistic sound design, although it does leave me wanting even more.

Rocketship (dir. Mathias Choo)

Though Rocketship first presents itself as a story about divorce from a young boy’s perspective, as the film progresses, it becomes clear that this is not the case. It is less about divorce and much more about a powerful mother-son relationship. Mathias Choo’s cinematography choices are simple, symmetrical and easy to digest, which makes the film very pleasurable to view. And while the reality of the world Samuel and his mother inhabit feel very fictionalised, the emotions which they feel are very real.

Rocketship isn’t reinventing the wheel but what it does do is tell a poignant story about a mother trying to love her son and a son attempting to fix what is irreparably broken. Something the film does very well is enter into a child’s psyche with immense respect for their perspective. Samuel’s motivation, plotting and action are all presented without judgement, and his desperate attempt at creating a moment between his parents is viewed through the lens of great urgency and importance. Samuel believes that his rockets might bring his parents back to the way things used to be and lead to them getting back together, and he believes it so strongly that I started to hope for it as well. But, of course, reality is much more crushing than that.

Samuel’s young actor, Issac Loong Zen Yu, is a standout in the short film. While some child actors can feel artificial and put up, Loong’s characterisation of Samuel feels incredibly realistic—especially the moments where he is by himself, asking Mother Mary for a favour in the way only a 10-year-old child could.

There are really only two characters in Rocketship: Samuel and his mother. Sure, his father’s presence looms large over the entire story, but really his significance is minute. The father’s influence on the story is passive. While Samuel’s mother spends most of the time berating him, it is obvious that this is due to the fact that she is grieving as well. But she listens to her son and shares his excitement with rockets. As the credits roll, we hear Samuel’s homemade rocketships shoot into the air, and both mother and son have found what was missing in each other.

Through the short, Choo has done an excellent job capturing a slice of an unconventional family beginning to heal together. The design of the frames gives a slightly fantastical feeling to the short, which seems fitting for the story that emerges partly from a young boy's simple imagination of the world around him.

Tellurian Drama (dir. Riar Rizaldi)

There are really only two characters in Rocketship: Samuel and his mother. Sure, his father’s presence looms large over the entire story, but really his significance is minute. The father’s influence on the story is passive. While Samuel’s mother spends most of the time berating him, it is obvious that this is due to the fact that she is grieving as well. But she listens to her son and shares his excitement with rockets. As the credits roll, we hear Samuel’s homemade rocketships shoot into the air, and both mother and son have found what was missing in each other.

Through the short, Choo has done an excellent job capturing a slice of an unconventional family beginning to heal together. The design of the frames gives a slightly fantastical feeling to the short, which seems fitting for the story that emerges partly from a young boy's simple imagination of the world around him.

Tellurian Drama (dir. Riar Rizaldi)

Of all the short films in this programme, Tellurian Drama is the most difficult to process. The lines between truth and fiction are blurred so heavily that it becomes impossible to separate what is factual from what has been made up. However, this is also what makes Riar Rizaldi’s film so compelling.

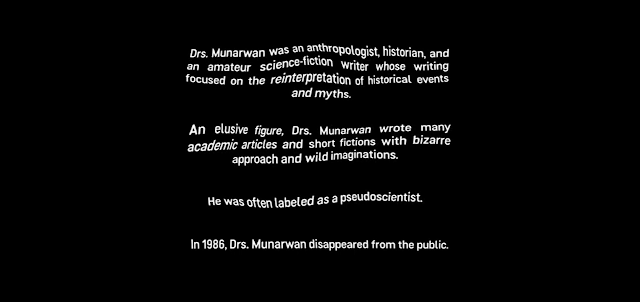

From the opening, Tellurian Drama makes it clear that some of the scientific claims quoted on screen are sometimes considered to be “pseudoscience”. The story feels like an alternate reality where almost everything is the same as in our universe, except for a few differences that are basically impossible to point out.

From the opening, Tellurian Drama makes it clear that some of the scientific claims quoted on screen are sometimes considered to be “pseudoscience”. The story feels like an alternate reality where almost everything is the same as in our universe, except for a few differences that are basically impossible to point out.

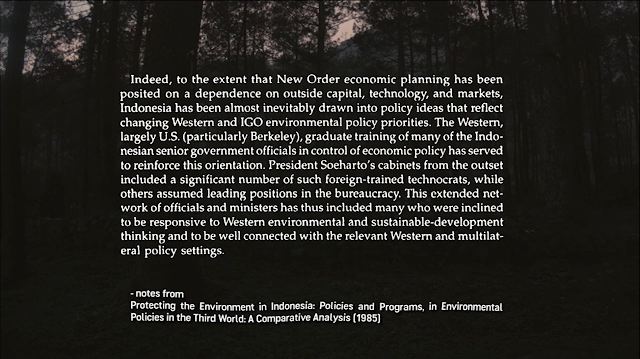

The film hinges on Indonesia’s past as a Dutch colony, and the Dutch colonisers’ need to build a radio which could communicate back to the Netherlands. This station, Radio Malabar, ends up being looted and abandoned during the Second World War, and in Tellurian Drama we find it an abandoned ruin. Rizaldi interweaves between showing the audience Radio Malabar’s state today and its surrounding nature, presenting excerpts from Drs. Munarwan’s 1986 article “Reconfiguring the Earth: Radio Malabar as a Geoengineering Imagination” through narration and provide historical context on the creation and usage of the radio station. Just like Munarwan, Tellurian Drama attempts to “reconstruct reality” by breathing new life into Radio Malabar in the form of docufiction.

Tellurian Drama’s sound design really stands out in the production of the short film. Rizaldi doesn’t just use generic rainforest soundscapes to signal to the audience where the story takes place, but uses sound as another way of communicating important messages. The buzzing noise of flying insects becomes intrusive, almost adopting the metaphorical role of the ancestral spirit of the ruins. Music is used sparingly, but whenever it is present, it draws full attention to itself. It is a stark contrast between the realism of the other sounds in the film, and give an otherworldly feel to the sequence. In the end Rizaldi chooses to focus on the visceral human influence on the Radio Malabar story, bookending the film with a six-minute extended sequence of an Indonesian man playing the zither and singing on the steps of the station.

Rizaldi’s film obsesses over communicating with the earth and using the earth as a communication device. The word “tellurian”, meaning “inhabiting the earth”, connects closely to Drs. Munarwan’s writing and alludes to the inherent fact that we as people have a symbiotic relationship with the planet we inhabit. The technological advancements we create, the colonial ruins we abandon and the power of indigenous pasts we often forget are all irrevocably of the earth and ever present throughout Tellurian Drama.

Tellurian Drama’s sound design really stands out in the production of the short film. Rizaldi doesn’t just use generic rainforest soundscapes to signal to the audience where the story takes place, but uses sound as another way of communicating important messages. The buzzing noise of flying insects becomes intrusive, almost adopting the metaphorical role of the ancestral spirit of the ruins. Music is used sparingly, but whenever it is present, it draws full attention to itself. It is a stark contrast between the realism of the other sounds in the film, and give an otherworldly feel to the sequence. In the end Rizaldi chooses to focus on the visceral human influence on the Radio Malabar story, bookending the film with a six-minute extended sequence of an Indonesian man playing the zither and singing on the steps of the station.

Rizaldi’s film obsesses over communicating with the earth and using the earth as a communication device. The word “tellurian”, meaning “inhabiting the earth”, connects closely to Drs. Munarwan’s writing and alludes to the inherent fact that we as people have a symbiotic relationship with the planet we inhabit. The technological advancements we create, the colonial ruins we abandon and the power of indigenous pasts we often forget are all irrevocably of the earth and ever present throughout Tellurian Drama.

The 31st edition of the Singapore International Festival (SGIFF) is happening from 26 Nov to 6 Dec 2020 both online and in cinemas. Visit their website for the programme lineup and to purchase tickets.

Written by Valerie Tan